Total variation

In mathematics, the total variation identifies several slightly different concepts, related to the (local or global) structure of the codomain of a function or a measure. For a real-valued continuous function  , defined on an interval [a, b] ⊂ ℝ, its total variation on the interval of definition is a measure of the one-dimensional arclength of the curve with parametric equation x ↦

, defined on an interval [a, b] ⊂ ℝ, its total variation on the interval of definition is a measure of the one-dimensional arclength of the curve with parametric equation x ↦  (x), for x ∈ [a,b].

(x), for x ∈ [a,b].

Contents |

Historical notice

The concept of total variation for functions of one real variable was first introduced by Camille Jordan in the paper (Jordan 1881).[1] He used the new concept in order to prove a convergence theorem for Fourier series of discontinuous periodic functions whose variation is bounded. The extension of the concept to functions of more than one variable however is not simple for some reasons.

Definitions

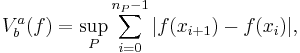

Total variation for functions of one real variable

The total variation of a real-valued (or more generally complex-valued) function  , defined on an interval

, defined on an interval ![[a , b]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) ⊂ℝ is the quantity

⊂ℝ is the quantity

where the supremum runs over the set of all partitions ![\scriptstyle \mathcal{P} =\left\{P=\{ x_0, \dots , x_{n_P}\}|P\text{ is a partition of } [a,b] \right\}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c696658d9fecb47cda18736320ebbee8.png) of the given interval.

of the given interval.

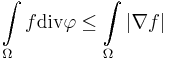

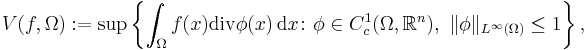

Total variation for functions of n>1 real variables

Let  be an open subset of ℝn. Given a function

be an open subset of ℝn. Given a function  belonging to

belonging to  , the total variation of

, the total variation of  in is defined as

in is defined as

where  is the set of continuously differentiable vector functions of compact support contained in

is the set of continuously differentiable vector functions of compact support contained in  , and

, and  is the essential supremum norm. Note that this definition does not require that the domain

is the essential supremum norm. Note that this definition does not require that the domain  ⊆ℝn of the given function is a bounded set.

⊆ℝn of the given function is a bounded set.

Total variation in measure theory

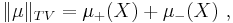

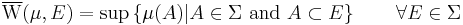

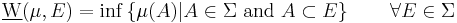

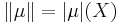

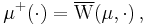

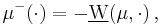

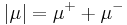

Following Saks (1937, p. 10), consider a signed measure  on a measurable space

on a measurable space  : then it is possible to define two set functions

: then it is possible to define two set functions  and

and  , respectively called upper variation and lower variation, as follows

, respectively called upper variation and lower variation, as follows

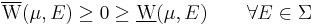

clearly

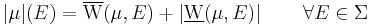

The variation (also called absolute variation) of the signed measure  is the set function

is the set function

and its total variation is defined as the value of this measure on the whole space of definition, i.e.

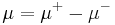

Saks (1937, p. 11) uses upper and lower variations to prove the Hahn–Jordan decomposition: according to his version of this theorem, the upper and lower variation are respectively a non-negative and a non-positive measure. Using a more modern notation, define

Then  and

and  are two non-negative measures such that

are two non-negative measures such that

The last measure is sometimes called, by abuse of notation, total variation measure.

If the measure  is complex-valued i.e. is a complex measure, its upper and lower variation cannot be defined and the Hahn–Jordan decomposition theorem can only be applied to its real and imaginary parts. However, it is possible to follow Rudin (1966, pp. 137–139) and define the total variation of the complex-valued measure

is complex-valued i.e. is a complex measure, its upper and lower variation cannot be defined and the Hahn–Jordan decomposition theorem can only be applied to its real and imaginary parts. However, it is possible to follow Rudin (1966, pp. 137–139) and define the total variation of the complex-valued measure  as follows

as follows

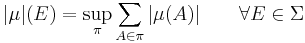

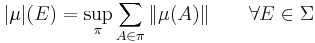

The variation of the complex-valued measure  is the set function

is the set function

where the supremum is taken over all partitions  of a measurable set

of a measurable set  into a finite number of disjoint measurable subsets.

into a finite number of disjoint measurable subsets.

The variation so defined is a positive measure (see Rudin (1966, p. 139)) and coincides with the one defined by 1.3 when  is a signed measure: its total variation is defined as above. This definition works also if

is a signed measure: its total variation is defined as above. This definition works also if  is a vector measure: the variation is then defined by the following formula

is a vector measure: the variation is then defined by the following formula

where the supremum is as above. Note also that this definition is slightly more general than the one given by Rudin (1966, p. 138) since it requires only to consider finite partitions of the space  : this implies that it can be used also to define the total variation on finitely-additive measures.

: this implies that it can be used also to define the total variation on finitely-additive measures.

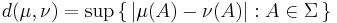

Total variation of probability measures

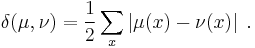

The total variation of any probability measure is exactly one, therefore it is not interesting as a means of investigating the properties of such measures. However, when μ and ν are probability measures, the total variation distance of probability measures can be defined as

and its values are non-trivial. Informally, this is the largest possible difference between the probabilities that the two probability distributions can assign to the same event. For a categorical distribution it is possible to write the total variation distance as follows

The total variational distance for categorical probability distributions is called statistical distance: sometimes, in the definition of this distance, the factor  is omitted.

is omitted.

Basic properties

Total variation of differentiable functions

The total variation of a differentiable function  can be expressed as an integral involving the given function instead of as the supremum of the functionals of definitions 1.1 and 1.2.

can be expressed as an integral involving the given function instead of as the supremum of the functionals of definitions 1.1 and 1.2.

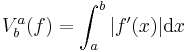

The form of the total variation of a differentiable function of one variable

The total variation of a differentiable function  , defined on an interval

, defined on an interval ![[a , b]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) ⊂ℝ, has the following expression if f' is Riemann integrable

⊂ℝ, has the following expression if f' is Riemann integrable

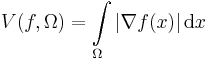

The form of the total variation of a differentiable function of several variables

Given a differentiable function  defined on a bounded open set

defined on a bounded open set  ⊆ℝn, the total variation of

⊆ℝn, the total variation of  has the following expression

has the following expression

Proof

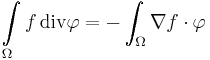

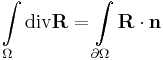

The first step in the proof is to first prove an equality which follows from the Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem.

Lemma

Under the conditions of the theorem, the following equality holds:

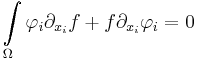

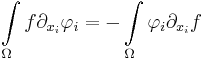

Proof of the lemma

From the Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem:

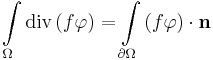

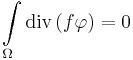

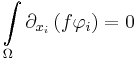

by subtituting  , we have:

, we have:

where  is zero on the border of

is zero on the border of  by definition:

by definition:

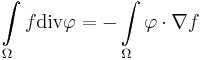

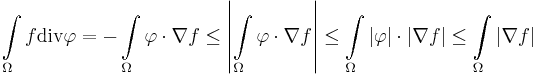

Proof of the equality

Under the conditions of the theorem, from the lemma we have:

in the last part  could be omitted, because by definition it's considerate supremum is at most one.

could be omitted, because by definition it's considerate supremum is at most one.

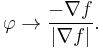

On the other hand we consider ![\theta_n:=\mathbb I_{\left[-N,N\right]}\frac{\nabla f}{\left|\nabla f\right|}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f276c776874f3ff4a2b3410e297bfff0.png) and

and  which is the up to

which is the up to  approximation of

approximation of  in

in  with the same integral. We can do this hence

with the same integral. We can do this hence  is dense in

is dense in  . Now again substituting into the lemma:

. Now again substituting into the lemma:

This means we have a convergent sequence of  that tends to

that tends to  as well as we know that

as well as we know that  . q.e.d.

. q.e.d.

It can be seen from the proof that the supremum is attained when

The function  is said to be of bounded variation precisely if its total variation is finite.

is said to be of bounded variation precisely if its total variation is finite.

Total variation of a measure

The total variation is a norm defined on the space of measures of bounded variation. The space of measures on a σ-algebra of sets is a Banach space, called the ca space, relative to this norm. It is contained in the larger Banach space, called the ba space, consisting of finitely additive (as opposed to countably additive) measures, also with the same norm. The distance function associated to the norm gives rise to the total variation distance between two measures μ and ν.

For finite measures on ℝ, the link between the total variation of a measure μ and the total variation of a function, as described above, goes as follows. Given μ, define a function  by

by

Then, the total variation of the signed measure μ is equal to the total variation, in the above sense, of the function φ. In general, the total variation of a signed measure can be defined using Jordan's decomposition theorem by

for any signed measure μ on a measurable space  .

.

Applications

Total variation can be seen as a non-negative real-valued functional defined on the space of real-valued functions (for the case of functions of one variable) or on the space of integrable functions (for the case of functions of several variables). As a functional, total variation finds applications in several branches of mathematics and engineering, like optimal control, numerical analysis, and calculus of variations, where the solution to a certain problem has to minimize its value. As an example, use of the total variation functional is common in the following two kind of problems

- Numerical analysis of differential equations: it is the science of finding approximate solutions to differential equations. Applications of total variation to this problems are detailed in the article "total variation diminishing"

- Image denoising: in image processing, denoising is a collection of methods used to reduce the noise in an image reconstructed from data obtained by electronic means, for example data transmission or sensing. Total variation denoising is the name for the application of total variation to image noise reduction; further details can be found in the paper (Caselles, Chambolle & Novaga 2007).

See also

Notes

- ^ According to Golubov & Vitushkin (2001).

Bibliography

- Arzelà, Cesare (7 maggio 1905), "Sulle funzioni di due variabili a variazione limitata (On functions of two variables of bounded variation)" (in Italian), Rendiconto delle sessioni della Reale Accademia delle scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna, Nuova serie IX (4): 100–107, JFM 36.0491.02, archived from the original on 2007-08-07, http://www.archive.org/stream/rendicontodelle04bologoog#page/n121/mode/2up.

- Jordan, Camille (1881), "Sur la série de Fourier" (in French), Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences 92: 228–230, JFM 13.0184.01, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k7351t/f227 (available at Gallica). This is, according to Boris Golubov, the first paper on functions of bounded variation.

- Hahn, Hans (1921) (in German), Theorie der reellen Funktionen, Berlin: Springer Verlag, pp. VII+600, JFM 48.0261.09, archived from the original on 2008-12-31, http://www.archive.org/details/theoriederreelle01hahnuoft.

- Vitali, Giuseppe (1908) [17 dicembre 1907], "Sui gruppi di punti e sulle funzioni di variabili reali (On groups of points and functions of real variables)" (in Italian), Atti dell'Accademia delle Scienze di Torino 43: 75–92, JFM 39.0101.05, archived from the original on 2009-03-31, http://www.archive.org/stream/attidellarealeac43real#page/228/mode/2up. The paper containing the first proof of Vitali covering theorem.

References

- Adams, C. Raymond; Clarkson, James A. (1933), "On definitions of bounded variation for functions of two variables", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 35: 824–854, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1933-1501718-2, JFM 59.0285.01, MR1501718, Zbl 0008.00602, http://www.ams.org/journals/tran/1933-035-04/S0002-9947-1933-1501718-2/home.html.

- Cesari, Lamberto (1936), "Sulle funzioni a variazione limitata (On the functions of bounded variation)" (in Italian), Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore, II 5 (3-4): 299–313, JFM 62.0247.03, MR1556778, Zbl 0014.29605, http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ASNSP_1936_2_5_3-4_299_0. Available at Numdam.

- Saks, Stanisław (1937), Theory of the Integral, Monografie Matematyczne, 7 (2nd ed.), Warszawa-Lwów: G.E. Stechert & Co., pp. VI+347, JFM 63.0183.05, MR1556778, Zbl 0017.30004, http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/kstresc.php?tom=7&wyd=10&jez=pl. (available at the Polish Virtual Library of Science). English translation from the original French by Laurence Chisholm Young, with two additional notes by Stefan Banach.

- Rudin, Walter (1966), Real and Complex Analysis, McGraw-Hill Series in Higher Mathematics (1st ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. xi+412, MR210528, Zbl 0142.01701.

External links

Theory

One variable

- Golubov, Boris I.; Vitushkin, Anatolii G. (2001), "Variation of a function", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=V/v096110

- "Total variation" on Planetmath.

Several variables

- Final comments of Anatolii Georgievich Vitushkin on the paper Golubov, Boris I.; Vitushkin, Anatolii G. (2001), "Variation of a function", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=V/v096110.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Arzelà variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=a/a013470.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Fréchet variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=f/f041400.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Hardy variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=h/h046400.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Pierpont variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/p072720.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Vitali variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=h/h046400.

- Golubov, Boris I. (2001), "Tonelli plane variation", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=t/t092990.

Measure theory

- Rowland, Todd, "Total Variation" from MathWorld..

- Jordan decomposition at PlanetMath..

Probability theory

- M. Denuit and S. Van Bellegem "On the stop-loss and total variation distances between random sums", discussion paper 0034 of the Statistic Institute of the "Université Catholique de Louvain".

Applications

- Caselles, Vicent; Chambolle, Antonin; Novaga, Matteo (2007), The discontinuity set of solutions of the TV denoising problem and some extensions, SIAM, Multiscale Modeling and Simulation, vol. 6 n. 3,, http://cvgmt.sns.it/papers/caschanov07/ (a work dealing with total variation application in denoising problems for image processing).

- Tony F. Chan and Jackie (Jianhong) Shen (2005), Image Processing and Analysis - Variational, PDE, Wavelet, and Stochastic Methods, SIAM, ISBN 0-89871-589-X (with in-depth coverage and extensive applications of Total Variations in modern image processing, as started by Rudin, Osher, and Fatemi).

![\lim\limits_{N\rightarrow\infty}\int\limits_\Omega f\text{div}\theta^*_n =

\lim\limits_{N\rightarrow\infty}\int\limits_\Omega\mathbb I_{\left[-N,N\right]}\nabla f\cdot\frac{\nabla f}{\left|\nabla f\right|}=

\lim\limits_{N\rightarrow\infty}\int\limits_{\mathbb I_{\left[-N,N\right]}} \nabla f\cdot\frac{\nabla f}{\left|\nabla f\right|} = \int\limits_\Omega\left|\nabla f\right|](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d72a73dc07cb983308dacd616e6f05c6.png)

![\varphi(t) = \mu((-\infty,t])~.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a31b7210dab5be48123ba220deb2a3e3.png)